“No synonym for God is so perfect as Beauty.”

“Nothing dollarable is safe. … One must labor for beauty as for bread.“

“Society speaks and all men listen, mountains speak and wise men listen.”

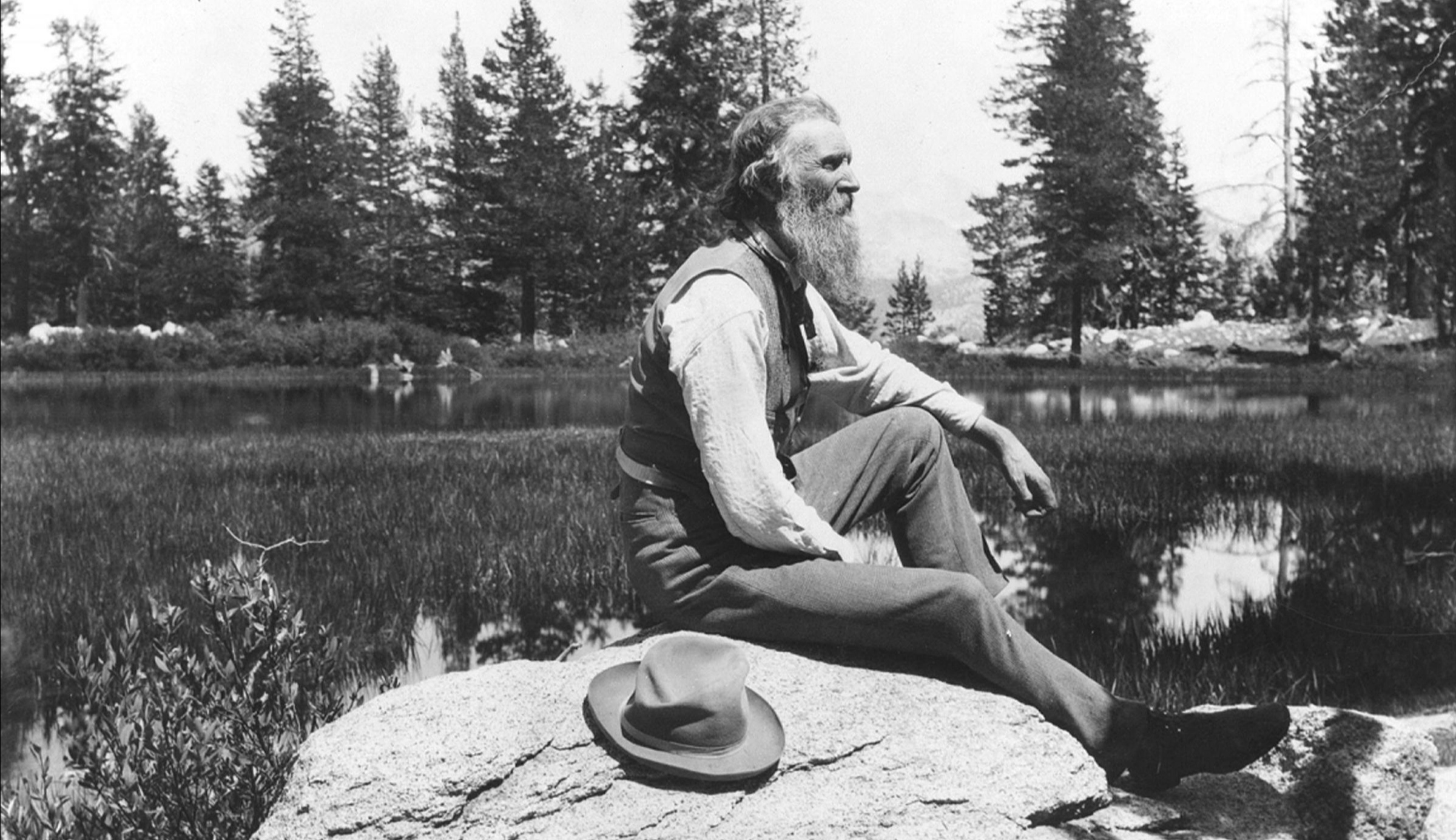

In a world of ticking clocks and relentless noise, John Muir’s voice still echoes—clear, calm, and deeply rooted in something ancient. He was not just a naturalist or explorer. He was a prophet of the mountains, a poet of the wilderness, a man who saw God not in a cathedral but in a grove of sequoias. For Muir, nature wasn’t a backdrop to life. It was life. And to live fully, he believed, one must go into the wild.

“The mountains are calling and I must go.”

With those nine words, Muir distilled the pull of the wild into a heartbeat. That line is more than famous—it’s sacred. It speaks to the hunger in all of us to escape, to return, to remember who we were before asphalt, emails, and the grind dulled our senses. For Muir, nature was not optional. It was essential. It was where one went to wake up.

Nature as Salvation

Muir wasn’t born into wilderness. He was born in Scotland in 1838 and raised under the harsh hand of a strict, religious father who believed hard labor was close to godliness. By the time Muir emigrated to America and grew into his own mind, he began replacing dogma with dirt, sermons with stars. He didn’t find divinity in doctrine—he found it in granite cliffs and wind-whipped pines.

“I’d rather be in the mountains thinking of God than in church thinking about the mountains.”

Muir’s spirituality was not abstract. It was tangible. You could feel it in the bark of a redwood, smell it in the alpine air, hear it in the thunder of waterfalls. Nature was not separate from the sacred. It was the sacred. He called the Sierra Nevada his “Range of Light.” He believed every tree was a prayer, every wildflower a hymn.

This wasn’t metaphor. Muir lived it. He would disappear for days, even weeks, walking into the backcountry with little more than some bread, a tin cup, and a notebook. He wasn’t escaping life. He was running toward it.

“In every walk with nature one receives far more than he seeks.”

What he sought was truth—not the kind printed in books or argued in halls, but the kind that reveals itself only in silence. Muir believed nature strips away pretense. Out in the wilderness, you’re no longer your job, your bank account, or your status. You’re just another creature trying to find your way. That humility, he said, is the beginning of wisdom.

Wilderness as Medicine

Long before “forest bathing” and wellness retreats, Muir knew that nature heals. After a factory accident nearly blinded him in his twenties, he vowed never to waste another day indoors. That brush with darkness opened his eyes to light in all its forms—sunlight, starlight, the inner light of wonder.

“Keep close to Nature’s heart… and break clear away, once in awhile, and climb a mountain or spend a week in the woods. Wash your spirit clean.”

There’s a purity in that advice. It’s not about conquering nature—it’s about surrendering to it. Muir didn’t climb mountains for bragging rights. He climbed because he needed to feel small. He needed to remember that human worries shrink when set against the backdrop of a glacial valley or a canyon carved over millennia.

He wrote of storms as blessings, of snow as silence incarnate. He didn’t fear the wild—he trusted it. “Storms,” he said, “make everything stronger.” That wasn’t just about trees. That was about people too.

Fighting for the Sacred

Muir wasn’t content to simply enjoy the wilderness—he fought to protect it. He founded the Sierra Club in 1892 and was a key force behind the creation of Yosemite National Park. His activism was rooted in reverence. For Muir, conservation wasn’t political—it was spiritual. He saw wilderness as the oldest cathedral, and he became one of its fiercest guardians.

“God has cared for these trees… but he cannot save them from fools.”

Muir was fierce when he had to be. When he saw logging companies stripping forests bare or developers eyeing sacred ground, he spoke with fire. He didn’t use spreadsheets or cost-benefit analyses. He used awe. He made people feel the loss. He made them see the soul of a forest, the character of a canyon.

His famous 1903 camping trip with President Theodore Roosevelt in Yosemite wasn’t just a photo-op. It was strategy. He wanted to show the President, firsthand, the grandeur that could be lost. And it worked. Roosevelt later set aside millions of acres for protection, thanks in part to Muir’s vision.

Living Wide Awake

There’s a deeper lesson in Muir’s life than simply “go outside.” His message was broader, richer. He was telling us to live deliberately, to be present, to choose wonder over cynicism, to make room for beauty. He wasn’t just about trees. He was about truth.

“The world is big and I want to have a good look at it before it gets dark.”

Muir didn’t want to tiptoe through life. He wanted to dive in. He reminds us that every sunrise is an invitation, every trail a sermon, every quiet moment beneath the trees a chance to remember who we really are. His life was a call to awaken—not just to the beauty around us, but to the beauty within us that gets buried under layers of routine and noise.

“When one tugs at a single thing in nature, he finds it attached to the rest of the world.”

This was Muir’s gospel: that nothing is isolated. The river is part of the mountain. The bird is part of the wind. And we, too, are part of that same web. The illusion that we are separate—from nature, from each other, from meaning itself—is what causes so much of our modern suffering. Muir didn’t just say that nature is good for us. He said it is us. To destroy it is to destroy ourselves.

And yet, his voice was not one of despair—it was one of hope. He believed that by reconnecting with the Earth, we could heal. Not just the land, but our spirits. Our culture. Our future.

A Map to the Sacred

Muir’s writings are more than observations; they’re maps—pointing us back to wonder, back to humility, back to the sacred. He doesn’t ask us to be perfect. He just asks us to pay attention. To go for a walk. To breathe the air deeply. To look at a tree long enough to see not just branches and bark, but the miracle of it.

“The clearest way into the Universe is through a forest wilderness.”

There’s something timeless about that truth. Long before science measured the impact of green spaces on mental health, Muir was already telling us: this is where you find your peace. Not in screens. Not in stuff. But in stillness. In the hush of the forest. In the hush of your own heart.

A Legacy That Grows

Today, the parks Muir helped protect remain some of the last untouched sanctuaries in a world spinning faster and burning brighter by the day. His words, too, endure—not as dusty quotes, but as living guides. They urge us to unplug, to care, to see. They remind us that awe is not naive; it’s necessary.

John Muir didn’t have all the answers. But he asked the right questions. What is a good life? What does it mean to belong to this Earth? What do we lose when we forget how to wonder?

He didn’t just ask them—he lived them. With muddy boots and a full heart. With eyes wide open and hands ready to fight for what mattered. He was a man who believed that beauty could be a revolution.

And maybe that’s what we need most now—not more data or more speed, but more reverence. More people willing to stop, listen, and fall back in love with the wild world.

Because in the end, Muir wasn’t just writing about trees. He was writing about being alive. Fully, fiercely, beautifully alive.

“This grand show is eternal. It is always sunrise somewhere; the dew is never all dried at once; a shower is forever falling; vapor is ever rising. Eternal sunrise, eternal dawn and gloaming, on sea and continents and islands, each in its turn, as the round earth rolls.”

That’s the gospel of the wild. That life is vast. Sacred. Ongoing. And we’re invited—every single day—to be part of it.

“And into the forest I go, to lose my mind and find my soul…“

****

~John Muir (1838–1914) was a Scottish-born American naturalist, writer, and conservationist known as the “Father of the National Parks.” He was a fierce advocate for the preservation of wilderness in the United States, playing a key role in the creation of Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks. A prolific writer, Muir’s soulful reflections on nature inspired generations to see the natural world as sacred and interconnected. He founded the Sierra Club in 1892, which became a powerful force in environmental advocacy. Muir believed that communion with nature was essential to the human spirit, famously writing, “The mountains are calling and I must go.”

Excellence Reporter 2025

Categories: Nature, Sustainability, Wisdom of Life

Hi Nicolae, I sure hope you will do a second book with a compilation of these! I print them all out to re-read. Have a great summer Blessings, Manuela

“Each of us is intended to be a blessing to all the earth: the animal world, the vegetable world, the mineral world, the human world.” Joel S. Goldsmith “La personne la plus importante est toujours celle qui est à l’instant en face de moi”. Maître Eckhar https://www.babelio.com/auteur/Maitre-Eckhart/28353t https://www.babelio.com/auteur/Maitre-Eckhart/28353

https://www.facebook.com/ppradervand/

https://gentleartofblessing.org/

http://pierrepradervand.com/

https://www.facebook.com/groups/316404038484282/

https://www.facebook.com/groups/711463475570039

LikeLike

It’s really great to see you cover the vision of John Muir, Nicolae. It’s because we treasure our one-and-only Mother Nature that we made “Her” an integral link to our GoldenRuleism website. The can in the name represents the first 3 letters of each of the words children, animals, and nature. The Team focuses on these 3 areas — which we feel most people most everywhere will — to varying degrees — give their personal support to. Thanks for providing us with a view into Mr. Muir’s wisdom. Earth Herself is our single most important common bond, and we — ALL OF US — must do what we can and should do to always protect and preserve Her. It’s important beyond measure that the children of the world come to realize — at the very earliest ages — that they live on “their” Mother Earth/Mother Nature — that all families owe their very existence to Her — that Mother Earth is the mother of all. Craig

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Craig!

LikeLike