“The kingdom of heaven is not a place

but a state of mind.”

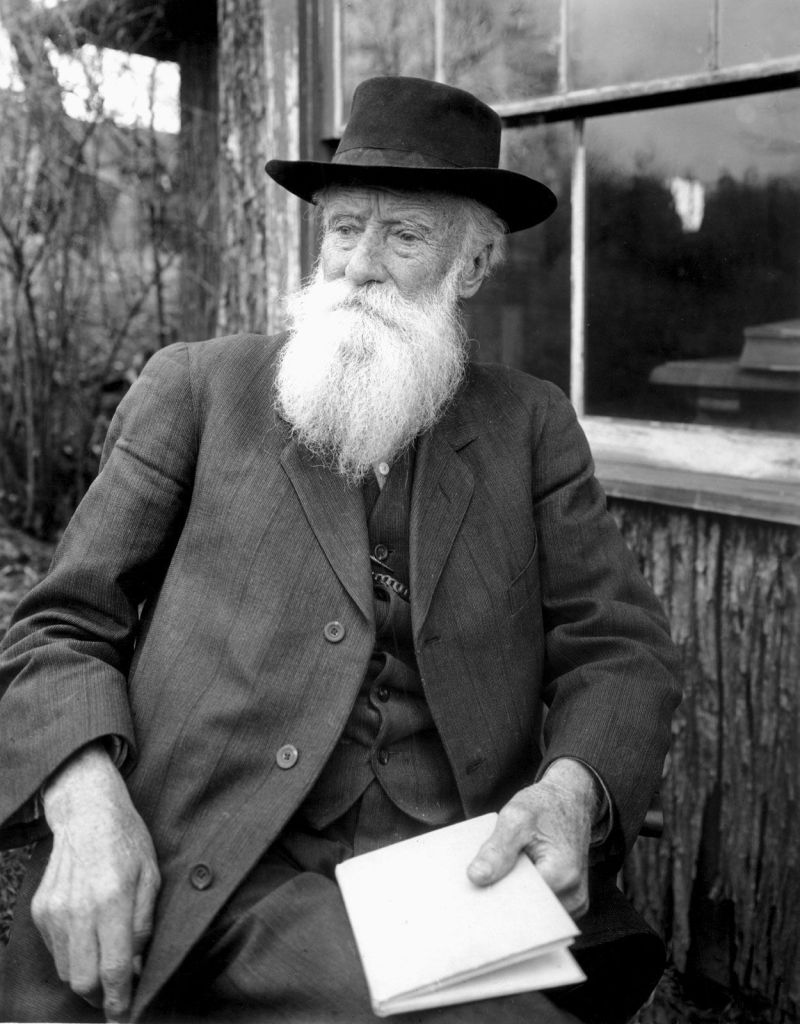

Life, to John Burroughs, was a sacred rhythm. It pulsed through the trees, rolled with the hills, whispered in the streams. It wasn’t something to master or escape from. It was something to belong to.

Burroughs did not write about nature as an outsider; he lived within it, folded into its seasons like a bird in its nest. He knew the soul of the land not through observation alone but through intimacy. To walk with John Burroughs was to remember that we are not apart from the world—we are of it. “I go to nature to be soothed and healed,” he wrote, “and to have my senses put in order.”

That was the heart of his belief: life is not a race to win but a wonder to feel. He taught that the deepest truths are not always found in books or cities, but in the slow unfurling of a fern, the hush before dawn, the way a bluebird flutters like a piece of sky made alive. Nature wasn’t just a backdrop—it was the divine revealed in soil and sunlight. “Joy in the universe, and keen curiosity about it all—that has been my religion,” he confessed, and you can feel the quiet reverence in those words. Not joy as escape, but as participation. Not curiosity as analysis, but as a reaching out of the soul.

Burroughs did not ask us to deny the grit of life—he was too honest for that. He saw the sorrow, the fleetingness, the decay. He watched the leaves fall and knew he, too, would one day drop from the branch. But he didn’t fear it. He understood that death was not an end but part of the music. “The secret of happiness is something to do,” he wrote, “some congenial work.” Life, to him, was not a thing to hoard or preserve. It was a fire to tend, a field to till, a note to sing while the breath is in you.

There was a deep humility in him. He did not pretend to know the meaning of it all. But he walked forward anyway, trusting in the quiet good that lay beneath things. He believed in being present, in being real. He mistrusted pretense, scorned cheap sentiment, and preferred a raw truth to a polished lie. And still, he was full of tenderness. There was nothing cynical in him. He could kneel beside a violet and find more spiritual nourishment there than in any sermon. “I still find each day too short for all the thoughts I want to think,” he wrote, “all the walks I want to take, all the books I want to read, and all the friends I want to see.”

Burroughs reminds us that life doesn’t have to be grand to be glorious. It just has to be honest. He lived in a cabin, wrote with simplicity, spoke plainly, and loved deeply. He teaches us, even now, that meaning is not something added to life—it is already there, if we’ll only slow down and notice. In the scent of pine, in the rhythm of chopping wood, in the sound of a child laughing or a sparrow singing in the hedge.

He believed that to see clearly was a kind of prayer. Not the kind that pleads, but the kind that praises by paying attention. In a world that rushes, that numbs, that distracts, Burroughs calls us back. Back to the essentials. To real things. “The lure of the distant and the difficult is deceptive,” he said. “The great opportunity is where you are.” That sentence is not just advice—it’s an invitation. To stop waiting. To live now.

He showed that you don’t need to cross oceans to find mystery—you can sit on your porch at dusk, watch the fireflies rise, and touch eternity. He wrote about the wind and the wheat with the same care others reserved for cathedrals. He made the small feel infinite, and in doing so, brought us closer to what really matters.

Burroughs’ strength was quiet. It came not from dominance or acclaim but from rootedness. He stayed true to his patch of earth, faithful to the unfolding of each season. His life teaches that you don’t have to chase greatness—you only have to love where you are, wholly and without pretense. There’s a kind of courage in that. The kind that doesn’t shout, but endures.

He believed the soul is nourished by the natural world not because it offers escape, but because it restores connection. Connection to ourselves. To each other. To time that isn’t broken into hours but into sunrises and bird migrations and the greening of fields after rain. He found in nature a mirror for the soul: wild and ordered, fleeting and eternal, imperfect yet utterly whole.

John Burroughs didn’t offer doctrine. He offered presence. He listened more than he spoke, and when he wrote, it felt like the earth itself was speaking—calmly, truthfully, without hurry. And maybe that’s what we need now more than ever. Not more speed. Not more noise. But to sit beside a stream and remember who we are when the world is quiet.

To read Burroughs is to remember the sacredness of the ordinary. It is to return to yourself. To the part that isn’t striving, pretending, achieving—but simply being. Being awake. Being grateful. Being alive.

In an age of distraction, Burroughs still whispers from the woods: “Leap, and the net will appear.” Trust your steps. Breathe deep. Let the earth hold you. Don’t be afraid to feel. Let life be what it is—fragile, fierce, fleeting—and let that be enough. Or rather, more than enough.

Because for John Burroughs, life was never a problem to be solved. It was a miracle to be welcomed. Not with fanfare or theory—but with open hands, and a heart wide enough to hold the sky.

****

~John Burroughs (1837–1921) was an American naturalist, essayist, and pioneer of the nature writing genre. Born in the Catskill Mountains of New York, he combined a deep scientific curiosity with a poet’s heart, crafting essays that celebrated the spiritual and philosophical richness of the natural world. A contemporary of Walt Whitman and a friend of Theodore Roosevelt, Burroughs wrote more than 20 books that helped shape America’s understanding of nature, simplicity, and purposeful living. Through quiet observation and honest prose, he inspired generations to slow down, pay attention, and find meaning in the everyday miracles of the earth.

Excellence Reporter 2025

Categories: Wisdom of Life

Nice write-up on Mr. Burroughs, Nicolae. A couple of lines jumped out at me: “…you can sit on your porch at dusk, watch the fireflies rise, and touch eternity.” I watched the fireflies when I was a kid in Illinois. There were multitudes of them then. Now — sadly — not nearly so many. But now, I often sit on the porch late in the day in Oregon and watch a myriad of bird species co-mingle at the bird feeders I have at the edge of the yard. To get to view these Mother Nature’s creatures in action is both calming and pleasing. Watching the birds takes me to the last line I’ll mention: “…find meaning in the everyday miracles of the earth.” Indeed, it’s a miracle there is an Earth — and a miracle that we get to live with Her. We humans tend to under-appreciate both. Craig

LikeLike