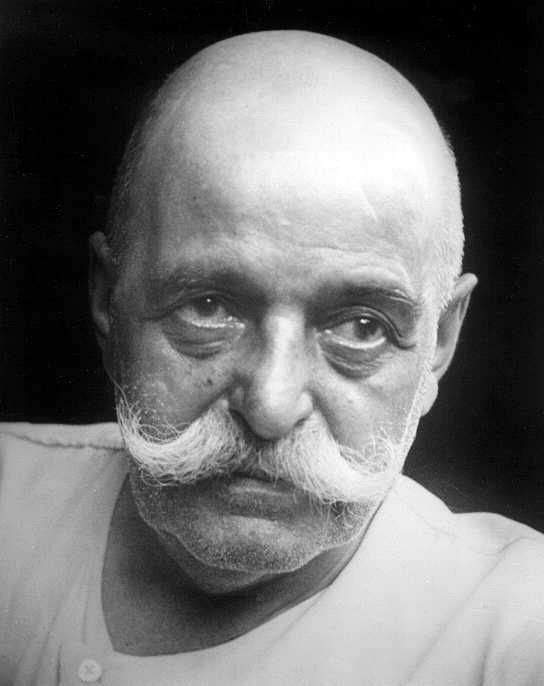

Most people spend their lives asleep. They may look awake, move, speak, strive, even suffer—but deep inside, they are asleep. This was the raw, unsettling truth at the heart of George Ivanovich Gurdjieff’s teaching. A mystic, philosopher, and spiritual teacher who lived between 1866 and 1949, Gurdjieff traveled the East and synthesized ancient esoteric traditions into a system that challenged modern Western assumptions about life, consciousness, and what it means to truly be.

His message was not sweet or comforting. It was a slap to the soul—a call to break the trance of automatic living.

“Man lives in sleep, and in sleep he dies.”

Gurdjieff did not mean physical sleep. He meant a kind of waking coma—a mechanical existence ruled by habits, reactions, conditioning, and unconscious impulses. We think we are free, but in truth, we are puppets pulled by strings we never bother to see.

The Illusion of the “I”

According to Gurdjieff, one of the most dangerous illusions modern people carry is the belief that they possess a unified, stable “I.” In reality, what we call the self is a shifting crowd of contradictory desires, moods, roles, and voices. One moment you’re generous. The next you’re jealous. You say one thing in the morning and contradict it by evening.

“Man has no permanent and unchangeable I. Every thought, every mood, every desire, every sensation says ‘I’. And in reality it is not I. It is only a thought, a mood, a desire or a sensation that speaks.”

This internal chaos means we cannot act with true will. We don’t choose our lives; we react to them. And so, Gurdjieff taught, the first step to waking up is to see this fragmentation. Not to fix it—yet—but to recognize it. To watch ourselves honestly and objectively, without judgment or justification.

This watching—this deep self-observation—is one of the cornerstones of Gurdjieff’s path.

The Work: A Way to Wake Up

Gurdjieff called his system The Work, or The Fourth Way—a path that unites the body, the emotions, and the mind. It is not the way of the monk (religion), the yogi (movement), or the fakir (asceticism), but a fourth way that works within the conditions of ordinary life.

“The Work consists in doing what is not natural to you. If you are lying, you must stop lying. If you are asleep, you must try to wake up.”

The Work demands struggle—but not aimless struggle. It requires intentional effort directed inward, toward integration and awareness. Simple tasks—eating, walking, talking—become opportunities to remember oneself, to interrupt the automatic flow and be present.

This is not easy. In fact, Gurdjieff was famous for putting his students under extreme pressure, discomfort, and contradiction to crack their self-image and force awareness. He once said, “Without struggle, no progress and no result. Every breaking of habit produces a change in the machine.”

His approach was not moralistic; it was alchemical. Life itself, with all its friction, could become a crucible for transformation—if we used it consciously.

Self-Remembering: The Inner Flame

At the heart of Gurdjieff’s teaching is the practice of self-remembering—a kind of inner division where you are aware both of the outer world and your inner presence. You are not just lost in the moment—you know that you are in the moment. You are watching yourself live, even as you live.

“Try to understand what the words ‘to remember oneself’ mean. It is not the same as ‘to think about oneself’… It means the capacity to divide attention, to be aware of oneself and what one is doing at the same time.”

This practice is subtle and slippery. The moment you grasp it, it slips away. But each glimpse opens something timeless. Even a few seconds of true self-remembering feel like a breath of real freedom.

It is a returning home to the spark of consciousness that exists before thought, identity, or reaction. And over time, this flame—if tended—grows into a deeper kind of being.

Shocks and Suffering: Food for the Soul

Gurdjieff did not shy away from the harsh realities of inner work. He taught that real growth requires shock—interruptions in our ordinary patterns. These shocks can be intentional, like the effort to self-remember, or accidental, like loss or suffering. But either way, they are necessary.

“Conscious labor and intentional suffering… are the only means by which man can attain to objective understanding.”

This may sound severe. But for Gurdjieff, suffering wasn’t about masochism or guilt. It was about seeing ourselves clearly, with all our contradictions, lies, and pretensions—and not turning away. It was about choosing to bear the truth, not because it’s comfortable, but because it’s real.

And through this process, the soul—what Gurdjieff called essence—can begin to grow. Not the false personality we usually operate from, but the deep, unborn core of what we truly are.

The Role of Conscious Community

Gurdjieff also knew that no one could do the Work alone. The ego is too cunning, the sleep too deep. He formed intentional communities—Schools of the Work—where students worked together under guidance, creating a field of shared effort and friction.

These communities weren’t soft places. They were often difficult, challenging, disorienting. But that was the point. They functioned like a mirror, exposing the parts of ourselves we usually hide or ignore. In that reflection, transformation became possible.

“A man cannot awaken by himself… but by the help of others who are awake.”

Today, many of Gurdjieff’s ideas live on in Fourth Way schools and related teachings. But the essence remains the same: to wake up, to remember oneself, to struggle consciously, and to turn ordinary life into a path of inner development.

Why Gurdjieff Still Matters

In a world of distraction, performance, and surface-level living, Gurdjieff’s message cuts to the bone. He doesn’t promise comfort or instant bliss. He offers something deeper: the possibility of being—authentic, awake, and whole.

“Only he who can take care of what belongs to others may have his own.”

That line, like many of his, seems cryptic at first. But it reveals a principle: that responsibility, attention, and presence are the foundation for any real inner possession. Until we can truly see and care for the moment we’re in—the people, duties, and tasks right before us—we can’t hope to hold anything more profound.

To live according to Gurdjieff is not to follow a dogma. It is to do the work, moment by moment, against the gravity of sleep. It is to build a soul where there was only personality. It is to trade illusion for truth, even when it hurts.

It is to wake up.

“Man is a machine, but a machine who can know he is a machine, and, knowing that, he may find the way to cease being a machine.”

That possibility—that fierce, radical hope—is the heart of Gurdjieff’s teaching. And it’s more relevant now than ever.

****

~George Ivanovich Gurdjieff (c. 1866–1949) was a mystic, philosopher, and spiritual teacher of Armenian and Greek descent. Born in the Caucasus region, Gurdjieff spent decades traveling through Central Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa in search of ancient spiritual knowledge. He synthesized what he discovered into a teaching known as The Fourth Way—a practical path of inner transformation designed for people living ordinary lives. Gurdjieff challenged conventional notions of self, free will, and consciousness, urging his students to “wake up” from mechanical living and pursue real being through self-remembering, conscious effort, and intentional suffering. His ideas continue to influence modern spirituality, psychology, and esoteric thought.

Excellence Reporter 2025

Categories: Wisdom of Life