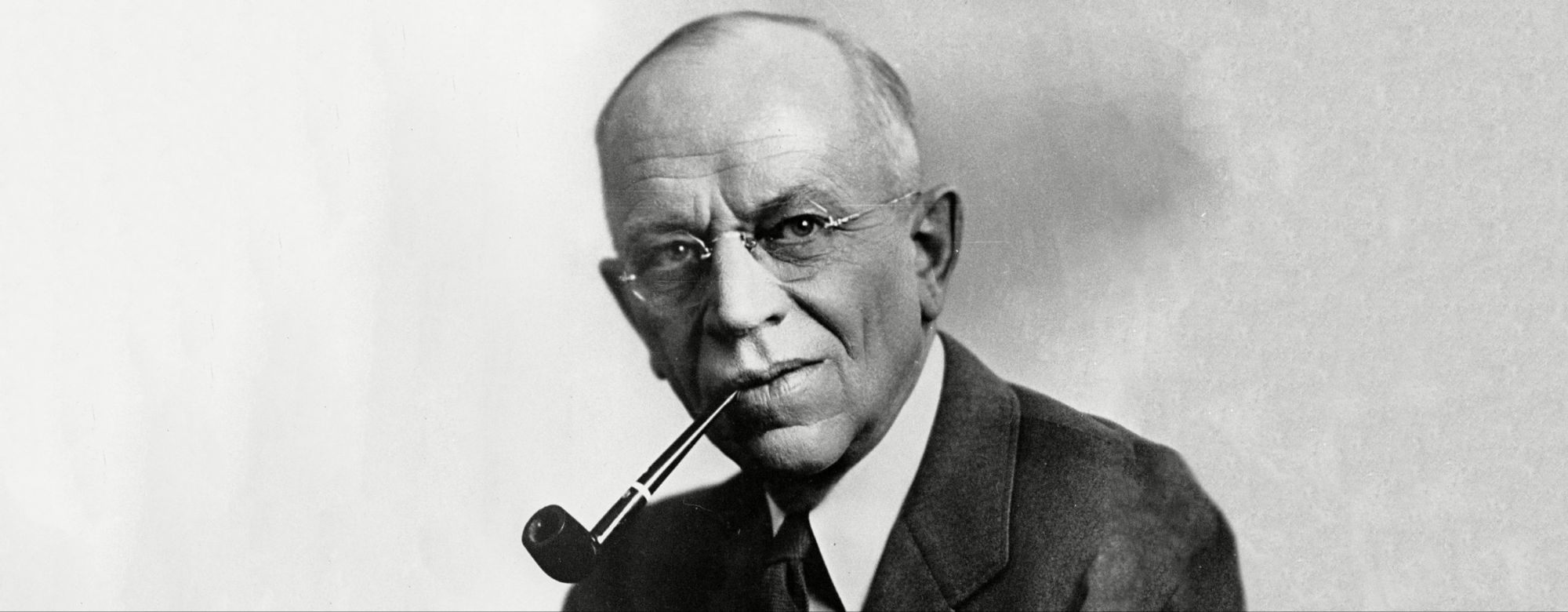

“Like winds and sunsets, wild things were taken for granted until progress began to do away with them. Now we face the question whether a still higher ‘standard of living’ is worth its cost in things natural, wild and free.”

Aldo Leopold was more than a conservationist. He was a philosopher, a poetic realist, and a man who understood that the health of the human spirit was tied—inevitably, irrevocably—to the health of the land. In a time when America was still intoxicated by industrial progress and frontier conquest, Leopold was already looking back with a sober eye and ahead with a broken heart. And yet, he never gave in to despair. He gave us hope, but not cheap hope. Hope grounded in action, reverence, and the humility to live rightly with the natural world.

To understand life through Leopold’s lens is to shift the frame entirely. It means rejecting the idea that nature exists to serve us. It means seeing ourselves not as conquerors of the land, but as “plain members and citizens of it.” That’s from his most enduring work, A Sand County Almanac, published posthumously in 1949. A book that reads like scripture for those seeking wisdom in wild things.

Leopold believed that ethics must evolve. Just as human ethics had expanded over centuries to include more people—across race, class, and nation—he believed the next step was to extend our ethical circle to include the land itself. “The land ethic simply enlarges the boundaries of the community to include soils, waters, plants, and animals, or collectively: the land.”

A Life Rooted in Observation

Leopold’s ethic didn’t emerge from theory. It grew from years of watching, walking, restoring. He began as a forester, trained in utilitarian land management—measuring board feet, maximizing yields. But as the decades wore on, he noticed a hollowness behind the numbers. Forests were thinning. Rivers were choking with silt. The quail stopped calling. He wasn’t just measuring loss; he was feeling it.

Out in the fields of Wisconsin, on an abandoned farm he and his family called The Shack, Leopold began to reimagine life. He planted trees. He tracked birds. He wrote essays about the cycles of the land. The land was no longer a commodity. It was kin. “There are some who can live without wild things, and some who cannot,” he wrote. Leopold made it clear which camp he belonged to.

Reverence Without Romanticism

Leopold didn’t worship nature from a distance. He knew it intimately—its violence, its suffering, its imperfections. But even in this knowledge, he found beauty. Not in the glossy postcard way, but in the patient unfolding of ecological interdependence.

Think of his essay “Thinking Like a Mountain.” In it, he recounts killing a wolf in his younger days, believing fewer predators meant more deer, and therefore, better land. But as he watched the green fire die in the wolf’s eyes, something shifted. “I realized then,” he wrote, “that neither the wolf nor the mountain agreed with such a view.” The mountain needed the wolf. The wolf checked the deer. The deer checked the forest. Everything had a role. And so did we.

But our role, as Leopold saw it, required restraint. Humility. A moral awakening. “We abuse land,” he wrote, “because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.”

The Spiritual Stakes

Leopold wasn’t just trying to save trees or protect wildlife. He was trying to redeem the human soul. He saw environmental degradation as a symptom of deeper disconnection. We had severed our ties to the wild, and in doing so, we had lost a piece of ourselves. He was writing not just for farmers or scientists, but for anyone searching for a deeper way to live.

This is where Leopold becomes not just a conservationist, but a guide for the soul. He offered a vision of life rooted in attention, humility, and service to something larger than oneself. A life not based on consumption, but on communion.

In a time when society races toward the artificial and the disposable, Leopold’s words cut through like gospel: “Harmony with land is like harmony with a friend; you cannot cherish his right hand and chop off his left.”

His ethic was not passive. It demanded effort. It demanded that we do the work—of restoring, observing, resisting the urge to dominate. “A thing is right,” he said, “when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.” Simple. Unflinching. And difficult.

Living the Land Ethic Today

What does it mean to live according to Aldo Leopold today?

It means re-learning how to see. To look at a field and not just see crops, but life systems—soil bacteria, pollinators, root networks, rainfall. It means choosing practices that regenerate rather than extract. It means challenging economic systems that reduce the land to units of profit.

But it also means smaller, quieter acts. Planting native flowers. Noticing the return of the swallows in spring. Reading the tracks in fresh snow. These are not insignificant. They are the foundations of a moral life, because they reconnect us to a larger story. One where we are not at the center.

Leopold knew that transformation would not come easily. “It must be slow,” he wrote. “It must be quiet. It must be done with love.”

A Final Reckoning—and Invitation

Aldo Leopold died of a heart attack in 1948 while fighting a wildfire near his home. He never lived to see the impact of his ideas. But his words endure because they speak to something primal and profound in us. A longing for home—not just a house or a town, but a rightful place in the order of things.

He didn’t give us easy answers. He gave us a challenge. To live more wisely, more humbly, more justly. Not just for the land, but for ourselves. Because, in the end, there is no real boundary between the two.

So, the question becomes: What kind of ancestor will you be? Will you take your place as a citizen of the land, or stand apart from it?

Leopold’s life suggests the answer lies not in grand gestures, but in daily choices. In learning to see the land not as scenery or resource, but as a community—alive, sacred, and deserving of our respect.

To live by his ethic is to live with courage and conscience. To see life not as a ladder to climb, but as a circle to protect.

And maybe, just maybe, to find in that circle a kind of peace.

****

~Aldo Leopold (1887–1948) was an American ecologist, forester, and environmental philosopher best known for developing the “land ethic,” a groundbreaking framework for ethical relationships between humans and the natural world. A pioneer in modern conservation, he authored the influential book A Sand County Almanac, which remains a cornerstone of environmental literature. Through his work as a professor, writer, and land steward, Leopold helped shape the fields of wildlife management, ecological restoration, and environmental ethics. His legacy continues to inspire movements for sustainability, biodiversity, and a more reverent way of living with the land.

Excellence Reporter 2025

Categories: Nature, Sustainability, Wisdom of Life