Virginia Woolf did not simply write about life—she dissected it, turned it over in her hands, exposed its bruises and its brilliance. Through her novels, essays, and diaries, she grappled with the ephemeral and the eternal, the ordinary and the cosmic. To look at life through Woolf’s eyes is to understand existence as a ripple of consciousness, where every moment matters and no feeling is too fleeting to matter.

The Stream of Consciousness: Life from the Inside Out

Woolf is often associated with the stream of consciousness technique, but that label alone doesn’t capture what she accomplished. For her, life was not a series of neat events—it was a flow, a pulse of inner experiences, where thought, sensation, and memory braided together.

In Mrs. Dalloway, Woolf writes:

“She felt very young; at the same time unspeakably aged. She sliced like a knife through everything; at the same time was outside, looking on.”

This line captures how Woolf viewed life: not as a static identity or linear story, but as a simultaneity of contradictions. You can be old and young, inside and outside, sharp and soft—all at once. Her characters don’t just live life; they witness themselves living it. That self-awareness, that internal narration, is life’s core for Woolf.

In a world constantly rushing forward, Woolf slowed things down—not to romanticize, but to render reality more honestly. She taught us that meaning isn’t just in milestones; it’s in a glance, a gesture, a sudden chill in the air. Life, according to Woolf, happens in the margins.

Ordinary Moments as Sacred

Woolf was obsessed with the “moment.” Not the historic or dramatic moment, but the quiet, almost invisible one. She believed these fragments made up the real substance of life.

In her diary, she once wrote:

“I have a deeply hidden and inarticulate desire for something beyond the daily life.”

And yet, paradoxically, she also believed the sacred was in daily life—if only we could see it clearly. Her novel To the Lighthouse is a masterclass in this philosophy. It’s ostensibly about a family vacation, but beneath that surface is a meditation on time, memory, and impermanence.

Take this line:

“What is the meaning of life? That was all—a simple question; one that tended to close in on one with years, the great revelation had never come. The great revelation perhaps never did come. Instead there were little daily miracles, illuminations, matches struck unexpectedly in the dark.”

That sentence is Woolf in a nutshell. She rejects the neat, grand answers. Life doesn’t offer “great revelations,” it offers “matches struck in the dark.” Those flashes—brief, bright, transient—are what give existence meaning. Not clarity, but illumination.

Feminine Consciousness and the Fight for Space

Woolf also examined how life felt differently depending on who you were. Gender, especially, shaped how one experienced time, freedom, and selfhood. In her famous essay A Room of One’s Own, she declared:

“A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.”

This wasn’t just about literature. Woolf was saying that to live authentically, women needed space—literal and metaphorical—to think, to feel, to exist without interruption. In her time, women’s lives were constrained by social norms and domestic expectations. Woolf saw this as a violation of the soul.

She recognized that consciousness, the very essence of life, could be distorted by power structures. A person who cannot think freely cannot live fully. So when Woolf spoke of needing a room, she was making a deeper point: the inner life deserves protection. And for many, that protection must be earned, not given.

Woolf’s feminism was not militant, but it was sharp. She didn’t just want equality; she wanted authenticity. She wanted a world in which everyone could access their full self—artistically, emotionally, intellectually.

Death, Time, and the Texture of Being

One cannot understand Woolf’s view of life without acknowledging how often she stared into the face of death. Death was not something outside life—it was woven into its texture. In The Waves, she writes:

“There is a square; there is an oblong. The players have taken their places. The lit and shadowed greens of the leaves flicker and pass. Time passes. Listen. Time passes.”

Time, in Woolf’s vision, is relentless but not cruel. It’s not an enemy—it’s the canvas on which life is painted. In Mrs. Dalloway, death haunts the day like a distant drumbeat. The suicide of Septimus Smith—a shell-shocked war veteran—is juxtaposed against Clarissa Dalloway’s shimmering party. Yet Woolf shows that both experiences belong to the same world, the same day, the same web of meaning.

“Death was defiance. Death was an attempt to communicate,” she writes.

Woolf’s own life ended by suicide, and it would be easy—too easy—to let that overshadow her philosophy. But Woolf didn’t see death as a failure. She saw it as part of the same mystery as birth, joy, madness, love. It was not separate from life; it was folded within it.

Art as Salvation

For Woolf, writing wasn’t a hobby—it was salvation. Art, she believed, was a way to freeze the flow of time, to give shape to chaos. Through art, we could impose coherence on the mess of memory and emotion.

In Moments of Being, Woolf contrasts two kinds of living: the “cotton wool” of unconscious routine and the rare, luminous “moments of being,” when the veil lifts and reality shines through.

“From this I reach what I might call a philosophy; at any rate it is a constant idea of mine; that behind the cotton wool is hidden a pattern… this is the meaning of all the things we have felt with great intensity.”

These moments—when the mundane breaks open and something eternal peeks through—are what Woolf lived for. They are why she wrote. Not to explain life, but to feel it more fully.

Conclusion: A Life Lived Awake

To see life through Virginia Woolf’s lens is to commit to a deeper form of living. One that resists simplification. One that doesn’t flinch from sorrow or turn away from beauty. One that dares to sit in silence and listen.

Woolf didn’t offer answers. She offered clarity. She taught us that life isn’t something to be conquered—it’s something to be noticed. The small things, the passing thought, the unspoken feeling—these are the real story.

In her own words:

“I am rooted, but I flow.”

That’s the paradox of life according to Woolf. We are grounded in a body, a place, a name—but inside, we are rivers of memory and meaning. And if we’re lucky, we learn to live not by chasing answers, but by bearing witness to the flood.

****

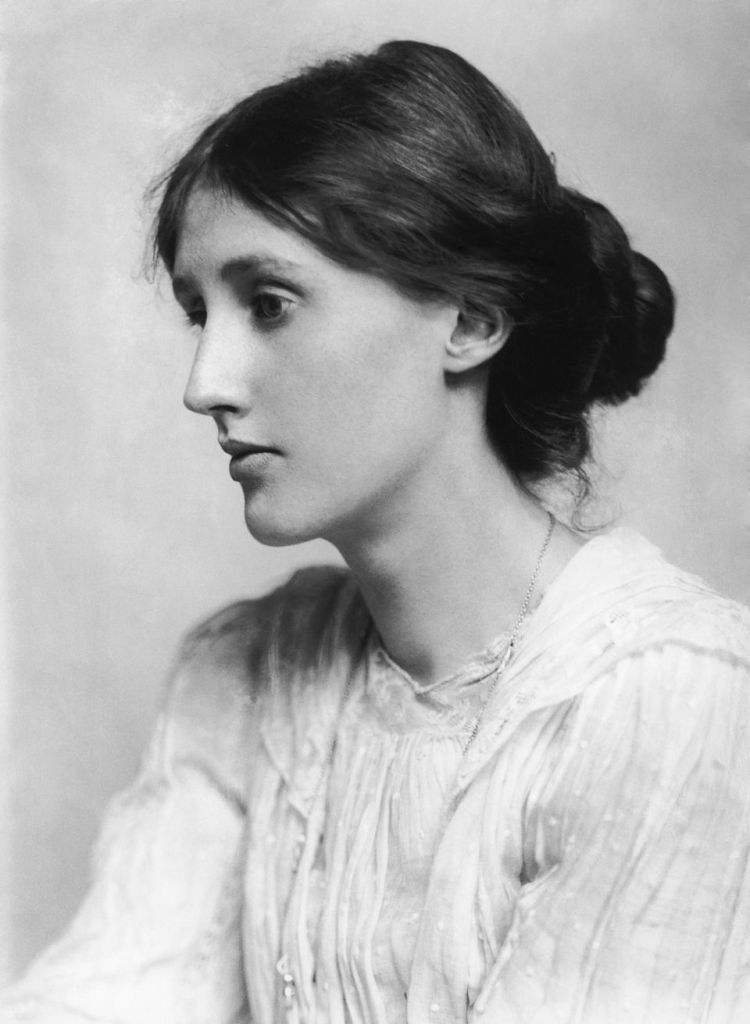

~Virginia Woolf (1882–1941) was a British novelist, essayist, and pioneer of modernist literature. Known for her groundbreaking narrative techniques—especially stream of consciousness—Woolf explored the depths of human thought, time, and identity in works like Mrs. Dalloway, To the Lighthouse, and The Waves. A key figure in the Bloomsbury Group and a passionate advocate for women’s intellectual freedom, her essay A Room of One’s Own remains a cornerstone of feminist thought. Despite lifelong struggles with mental illness, Woolf left behind a legacy of profound insight into the inner life and the subtle beauty of the everyday.

Excellence Reporter 2025

Categories: Wisdom of Life