“Happiness,

not in another place but this place…

not for another hour,

but this hour.”

“After you have exhausted what there is in business, politics, conviviality, and so on –

have found that none of these finally satisfy, or permanently wear – what remains?

Nature remains.”

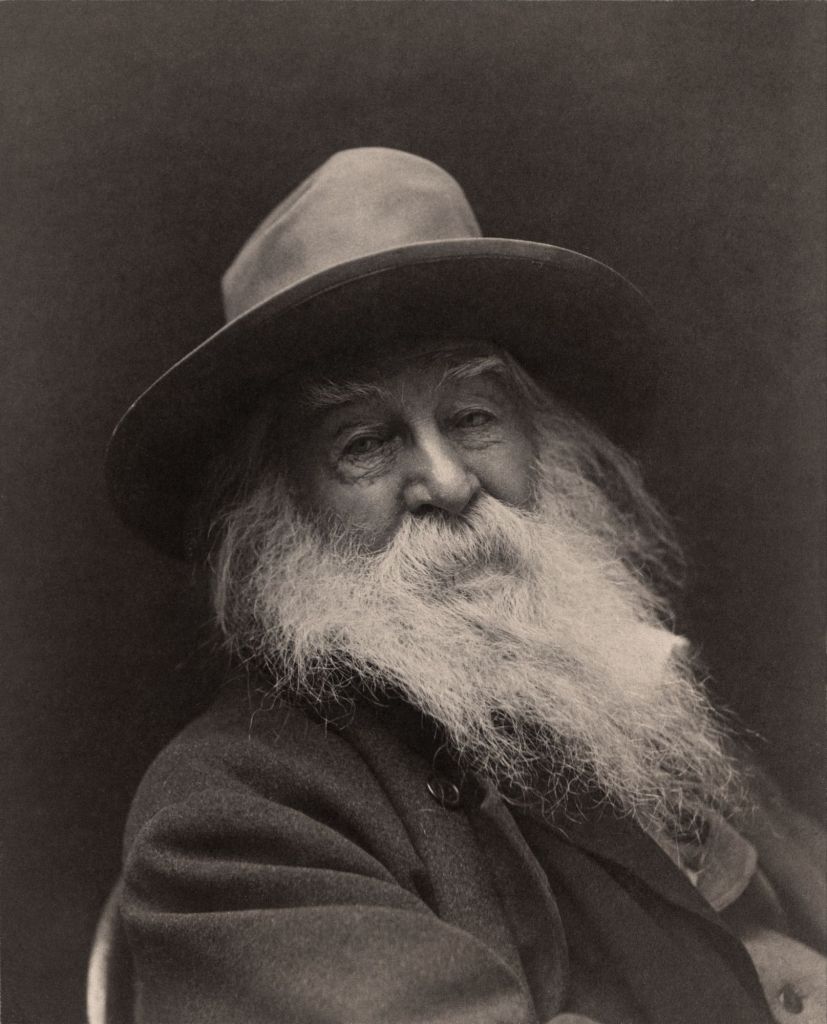

Walt Whitman didn’t whisper about life. He sang it—loud, bare-chested, unfiltered. To him, life wasn’t a puzzle to be solved but a miracle to be embraced. With arms flung wide, he invited the world in: the dirt, the sun, the stranger on the street, the wounded soldier, the flowing river, the sigh of a lover, the breath of a tree. “I celebrate myself, and sing myself,” he wrote in the opening line of Leaves of Grass, a book that would become one of the most thunderous declarations of selfhood and aliveness in American literature.

Whitman saw life as a sacred current that runs through everything—human and non-human, grand and minute. He stripped life of its artificial hierarchies. The grass beneath your feet was as holy to him as the stars above. He asked, “What is the grass?” and answered with layered wonder: maybe it’s the handkerchief of the Lord, maybe the uncut hair of graves. Life, for Whitman, was mystical but not distant. It pulsed through the blood, whispered through the leaves, stood naked and unashamed in the sun.

This wasn’t idle poetry. It was philosophy set ablaze. Whitman wrote, “Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself, (I am large, I contain multitudes.)” That line wasn’t just about poetry. It was about living without shame or apology. Life, in his eyes, wasn’t tidy. It was a glorious sprawl of contradictions, a mosaic of impulses, doubts, yearnings, and certainties. He urged us to embrace every fragment of who we are—our darkness and our light, our strength and our confusion.

Whitman didn’t just write about life; he paid attention to it. He walked the streets of Manhattan and Washington, not as a detached observer but as a participant. He volunteered in hospitals during the Civil War, tending to wounded soldiers, writing letters for them, witnessing their pain. In those moments, life was brutal, but never meaningless. To him, even suffering had dignity. He once said, “I am the poet of the body and I am the poet of the soul.” He refused to separate the two.

To live, for Whitman, was to live fully, with every nerve exposed to the world. He wanted to taste, to touch, to breathe in the rawness of being. He found joy in the ordinary—a carpenter’s hands, a child’s laugh, a ferry ride. In a time when industrialization was speeding everything up, Whitman slowed things down and paid reverent attention. “I loaf and invite my soul,” he wrote. There was no urgency to prove one’s worth. Worth was already intrinsic. Being was enough.

He loved America not blindly, but as one loves a flawed family—deeply and with hope. His poetry painted the country not as an abstract ideal but as a living, breathing mosaic of individuals: laborers, mothers, immigrants, soldiers, lovers. In “Song of Myself,” he declared, “I am of old and young, of the foolish as much as the wise.” He believed in unity, not uniformity. His America was inclusive, sprawling, diverse. Everyone had a place in his poem, in his vision.

There’s a reason Leaves of Grass feels like a sacred text to many. Whitman managed to bring the spiritual down to earth. He democratized the divine. No gatekeepers, no temples needed. A blade of grass, the curve of a hip, the wind on your face—these were portals to the eternal. “Divine am I inside and out,” he wrote. That wasn’t ego; that was liberation. He wanted every reader to feel the same holiness burning in their bones.

His work pulses with a deep, contagious optimism—not naïve, but defiant. He believed in the human spirit, even when history gave him every reason to despair. He lived through war, political upheaval, personal illness, and rejection. Yet he remained faithful to the joy of existence. “The powerful play goes on, and you may contribute a verse,” he declared. That line alone has launched a thousand lives in new directions. It reminds us: you matter. Your voice matters. You are part of the song.

Whitman’s life and work remind us to slow down and look closer. To really see the world, not rush past it. In a time where speed and productivity often eclipse presence, Whitman calls us back to the sacred ordinary. He said, “Happiness, not in another place but this place… not for another hour, but this hour.” That’s not just good poetry. It’s good living.

To follow Whitman is to walk barefoot through your own life—to feel it all, let it move through you, and greet each sensation, each person, with full presence. He invites us to say yes to life—even its hardest chapters. To stand tall in our nakedness, in our uncertainty, in our hope. To recognize that we, too, are part of the vast, breathing poem of existence. And if we dare to live fully, as he did, we don’t just read his poetry. We become it.

And isn’t that the heart of it? That life is not something to merely endure or manage, but something to sing with your whole chest. To love wildly, to lose deeply, to fall down and rise again with grass stains and soul scars. Whitman teaches us that it’s all holy—the heartbreak and the healing, the silence and the song.

In the end, Whitman gave us more than verse. He gave us a way of being. A way to meet life head-on with an open heart, to taste the salt of our tears and the sweetness of our joy with equal reverence. He reminded us that the divine is not elsewhere—it is here, in this breath, this step, this moment. To live according to Whitman is to let your soul sing, to find beauty in the rawness of being, and to love this life not because it is perfect, but because it is ours.

****

~Walt Whitman (1819–1892) was an American poet, essayist, and journalist, best known for his groundbreaking poetry collection Leaves of Grass. Born in Long Island, New York, and raised in Brooklyn, Whitman worked as a teacher, printer, and newspaper editor before devoting himself to poetry. His work broke with traditional forms, celebrating the body, nature, democracy, and the individual spirit with bold free verse and a radical sense of inclusivity. Often called the father of American poetry, Whitman’s themes of selfhood, sensuality, and universal connection made him a literary icon and spiritual guide for generations. His voice was one of deep compassion, fierce honesty, and unshakable belief in the sacredness of everyday life.

Excellence Reporter 2025

Categories: Wisdom of Life