“Peace of mind is that mental condition in which you have accepted the worst.”

“To glorify the past and paint the future is easy,

to survey the present and emerge with some light and understanding is difficult.”

“The wise man reads both books and life itself.”

We all have obligations and duties toward our fellow men. But it does seem curious enough that in modern neurotic society, men’s energies are consumed in making a living and rarely in living itself. It takes a lot of courage for a man to declare, with clarity and simplicity, that the purpose of life is to enjoy it. There is so much to love and to admire in this life that it is an act of ingratitude not to be happy and content in this existence.

Besides the noble art of getting things done, there is the noble art of leaving things undone. The wisdom of life consists in the elimination of non-essentials. Sometimes it is more important to discover what one cannot do, than what one can do.

So much of unhappiness, it seems to me, is due to nerves; and bad nerves are the result of having nothing to do, or doing a thing badly, unsuccessfully or incompetently. Of all the unhappy people in the world, the unhappiest are those who have not found something they want to do. True happiness comes to those who do their work well, followed by a refreshing period of rest. True happiness comes from the right amount of work for the day. The busy man is never wise and the wise man is never busy.

Anyone who wishes to learn to enjoy life must find friends of the same type of temperament, and take as much trouble to gain and keep their friendship as wives take to keep their husbands. Hope is like a road in the country; there was never a road, but when many people walk on it, the road comes into existence.

The man who has not the habit of reading is imprisoned in his immediate world, in respect to time and space. His life falls into a set routine; he is limited to contact and conversation with a few friends and acquaintances, and he sees only what happens in his immediate neighbourhood. From this prison there is no escape. But the moment he takes up a book, he immediately enters a different world, and if it is a good book, he is immediately put in touch with one of the best talkers of the world. This talker leads him on and carries him into a different country or a different age, or unburdens to him some of his personal regrets, or discusses with him some special line or aspect of life that the reader knows nothing about. An ancient author puts him in communion with a dead spirit of long ago, and as he reads along, he begins to imagine what the ancient author looked like and what type of person he was. There are no books in this world that everybody must read, but only books that a person must read at a certain time in a given place under given circumstances and at a given period of his life. The purpose of a short story is … that the reader shall come away with the satisfactory feeling that a particular insight into human character has been gained, or that his (or her) knowledge of life has been deepened, or that pity, love or sympathy for a human being is awakened.

The outstanding characteristic of Western scholarship is its specialization and cutting up of knowledge into different departments. The over-development of logical thinking and specialization, with its technical phraseology, has brought about the curious fact of modern civilization, that philosophy has been so far relegated to the background, far behind politics and economics, that the average man can pass it by without a twinge of conscience. The feeling of the average man, even of the educated person, is that philosophy is a “subject” which he can best afford to go without. This is certainly a strange anomaly of modern culture, for philosophy, which should lie closest to men’s bosom and business, has become most remote from life. It was not so in the classical civilization of the Greeks and Romans, and it was not so in China, where the study of wisdom of life formed the scholars’ chief occupation. Either the modern man is not interested in the problems of living, which are the proper subject of philosophy, or we have gone a long way from the original conception of philosophy. For a Westerner, it is usually sufficient for a proposition to be logically sound. For a Chinese it is not sufficient that a proposition be logically correct, but it must be at the same time in accord with human nature.

In contrast to logic, there is common sense, or still better, the Spirit of Reasonableness. The critical mind is too thin and cold, thinking itself will help little and reason will be of small avail; only the spirit of reasonableness, a sort of warm, glowing, emotional and intuitive thinking, joined with compassion, will insure us against a reversion to our ancestral type. Only the development of our life to bring it into harmony with our instincts can save us. I consider the education of our senses and our emotions rather more important than the education of our ideas. Only he who handles his ideas lightly is master of his ideas, and only he who is master of his ideas is not enslaved by them.

The most bewildering thing about man is his idea of work and the amount of work he imposes upon himself, or civilization has imposed upon him. All nature loafs, while man alone works for a living. The three great American vices seem to be efficiency, punctuality, and the desire for achievement and success. They are the things that make the Americans so unhappy and so nervous. A man who has to be punctually at a certain place at five o’clock has the whole afternoon ruined for him already.

“The Chinese do not draw any distinction between food and medicine.”

The simplicity of life and thought is the highest and sanest ideal for civilization and culture, that when a civilization loses simplicity and the sophisticated do not return to un-sophistication, civilization becomes increasingly full of troubles and degenerates. Man then becomes the slave of the ideas, thoughts, ambitions and social systems that are his own product. Our life is too complex, our scholarship too serious, our philosophy too somber, and our thoughts too involved. This seriousness and this involved complexity of our thought and scholarship make the present world such an unhappy one today.

I can see no other reason for the existence of art and poetry and religion except as they tend to restore in us a freshness of vision and more emotional glamour and more vital sense of life. The decay of religion is due to the pedantic spirit, in the invention of creeds, formulas, articles of faith, doctrines and apologies. We become increasingly less pious as we increasingly justify and rationalize our beliefs and become so sure that we are right. With the predominance of economic problems and economic thinking, which is overshadowing all other forms of human thinking, we remain completely ignorant of, and indifferent to, a more humanized knowledge and a more humanized philosophy, a philosophy that deals with the problems of the individual life.

Love of one’s fellowmen should not be a doctrine, an article of faith, a matter of intellectual conviction, or a thesis supported by arguments. The love of mankind which requires reasons is no true love. This love should be perfectly natural, as natural for man as for the birds to flap their wings. It should be a direct feeling, springing naturally from a healthy soul, living in touch with Nature. Love is an immortal wound that cannot be closed up. A person loses something, a part of her soul, when she loves someone. And she goes about looking for that lost part of her soul, for she knows that otherwise she is incomplete and cannot be at rest. It is only when she is with the person she loves that she becomes complete again in herself; but the moment he leaves, she loses that part which he has taken with him and knows no rest till she has found him once more.

“I like spring, but it is too young. I like summer, but it is too proud. So I like best of all autumn, because its leaves are a little yellow, its tone mellower, its colours richer, and it is tinged a little with sorrow and a premonition of death. Its golden richness speaks not of the innocence of spring, nor of the power of summer, but of the mellowness and kindly wisdom of approaching age. It knows the limitations of life and is content. From a knowledge of those limitations and its richness of experience emerges a symphony of colours, richer than all, its green speaking of life and strength, its orange speaking of golden content and its purple of resignation and death.”

“There is something in the nature of tea that leads us into a world of quiet contemplation of life.”

“What can be the end of human life except the enjoyment of it?”

“I have done my best. That is about all the philosophy of living one needs.”

***

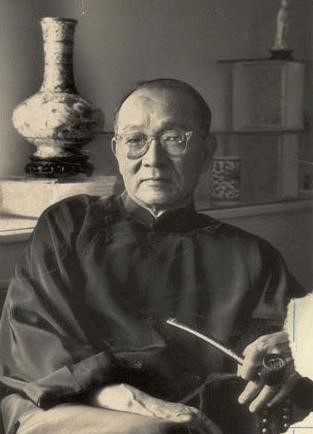

~Lin Yutang was a Chinese inventor, linguist, novelist, philosopher, and translator. He had an informal style in both Chinese and English, and he made compilations and translations of the Chinese classics into English. Some of his writings criticized the racism and imperialism of the West.

Excerpts from Lin Yutang, The Importance of Living

©Excellence Reporter 2024

Categories: Wisdom of Life